Children’s author Kimberly Willis Holt finds seeds for story ideas in her flower garden. Coming from a long line of gardeners, Kimberly says, “It’s in my genes. It’s only natural that as I write, gardening enters, not only in content but in process.”

Kimberly cultivates her writing process as carefully as she cultivates the garden in her Texas backyard, and both are fruitful. She’s written nine novels for young readers, four picture books, plus a six-volume chapter book series drawn from her military childhood. Her novel, When Zachary Beaver Came to Town, won a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

The seed for her latest book, Blooming at the Texas Sunrise Motel, came to Kimberly when she was working in her garden, purposefully mulling over ideas for a story about a girl. She thought it would be interesting to write about a modern Heidi, the title character of Johanna Spyri’s nineteenth-century classic.

The seed for her latest book, Blooming at the Texas Sunrise Motel, came to Kimberly when she was working in her garden, purposefully mulling over ideas for a story about a girl. She thought it would be interesting to write about a modern Heidi, the title character of Johanna Spyri’s nineteenth-century classic.

When Blooming at the Texas Sunrise Motel was finished, Kimberly sent the manuscript to her daughter, Shannon, who reads all her mother’s manuscripts before they go to final editing. Shannon said the finished book reminded her of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden.

“I have a section of my garden that is my secret garden, says Kimberly, “and I was in that part of the garden when I got the idea.”

When a story idea takes root, the real work of Kimberly’s writing process begins. She hones the story methodically, turning ideas into words, growing words into stories.

“I get a lot of ideas for stories that are not fully baked, and I’ll put them in a notebook. That puts it somewhere while I can think about it,” she says. “For the book I’m writing now, I got the idea … it may have been ten years ago. I put it in a notebook, and now’s the time I want to write it.”

Kimberly’s writing process begins with character sketches, and then researching the setting to get a feel for the location of a story. When those are done, she uses pen and notebook to write her first draft, aiming for a thousand to fifteen hundred words each day.

“I try to do it first thing in the morning when I’m fresh, when my editor cap is not on,” she says. “I write my first draft quickly, and I write every day until I’m done. I take Sunday off, but I stay connected to the story. That keeps me fresh, keeps me excited about the story.”

She writes by hand each day, then types what she’s written into her computer the following day while her ideas are still fresh—and, she says, while she can still read her handwriting.

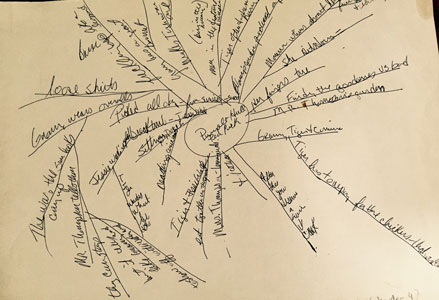

At this stage Kimberly uses two techniques. For brainstorming, she uses a technique called “webbing” or “branching.” She credits her use of this technique to a book titled Writing on Both Sides of the Brain by Henriette Anne Klauser. For structure, Kimberly builds her first draft using Aristotle’s Incline, particularly as described by Robert J. Ray in the revised and updated version of The Weekend Novelist.

“These are books that have meant a lot to me that I keep returning to. I’m always open to what another writer has found successful and looking at other writing books for something I can learn,” she says.

Aristotle’s Incline breaks down plot into acts and turning points. Act 1 introduces the characters and setting and ends with the first turning point. In Act 2 the story reaches its midpoint, while conflict builds, and characters grow deeper, ending with the second turning point. Conflict grows stronger in Act 3 until the catharsis or climax and ends with a wrap-up scene.

Kimberly builds her story on this basic structure, first writing the opening scene, then the wrap-up, followed by the catharsis, the midpoint, then the two turning points. With the key scenes and plot points in place, she is ready to begin writing the manuscript, fleshing out the story around the framework she has created from beginning to end.

Kimberly Willis Holt uses a technique called “webbing” or “branching” to brainstorm ideas for scenes and characters in her books.

Webbing comes into play throughout Kimberly’s writing process, as a way to brainstorm. Webbing begins with writing a central idea in the middle of the page and circling it. Kimberly then writes related words as they come to mind, connecting them with lines, branching off each other or back to the central word, until her page is full of words, all raw material for her creation.

“I web a few minutes before I start writing each scene. Usually a sequence emerges as I’m doing the webbing. I see the scene play out in my head.”

Kimberly used this technique to create a memorable scene in When Zachary Beaver Came to Town. While researching for the book, Kimberly interviewed a woman whose father had been a cotton farmer.

“She said the nicest time in the summer is when the ladybugs arrived,” Kimberly says. “She told me they came on the train in burlap sacks, inside crates.” The farmers would release the ladybugs into the fields. Ladybugs are friendly to the cotton crop, eating the eggs of the destructive bollworm.

“She told me it was the most beautiful sight to see ladybugs take flight when they’re released,” Kimberly says. “I knew I had to use that (in the book) but I didn’t know how, so I started webbing with ‘ladybugs’ in the middle of my page. I branched off that word with ‘crates, burlap sacks, trains, men, workers, cotton fields, dusk.’ Then I started thinking maybe they’ll be playing music, so I wrote ‘Mozart.’ Then I put the kids’ names down. Maybe Zachary will be there too, so then I thought maybe it would be called the ‘Ladybug Waltz.’”

And it was.

She says webbing is simple but powerful. When she leads writing workshops, she advises students to “have fun and be messy” while brainstorming with this or any method.

Kimberly emphasizes that during her brainstorming and when writing her first draft, she gets the story and her initial ideas on the page first, saving edits and changes for the multiple drafts she will create when rewriting. After taking a break from the manuscript for about two weeks, she reads through the entire manuscript without making any edits. She calls this, “the most painful read of the whole process.”

Next comes the process she calls “whittling,” in which she rewrites draft after draft, each one focused on one element of the story. First, she reads for structure to see if the story structure works and rewrites as needed. Next, she works on characters, one at a time.

“I dedicate a draft for every major character and most of the minor ones, too,” Kimberly says. “Each one gets their own draft. It helps me see who’s in each scene. Should they be there? should they say more?”

The next draft is for setting, which Kimberly thinks of as another character in her stories. Subsequent drafts include one for sensory details, one for similes and metaphors, and one for verbs and nouns, making sure the words she chooses are strong and effective.

She returns to webbing in the rewriting process to help her go deeper to flesh out scenes and characters. “I’m an underwriter rather than an over writer. My first drafts are very lean, half the word count of the final version. I build up, rather than trim away.”

As with gardening, sometimes trimming and weeding are necessary too. Not all ideas, scenes, or characters grow to fit the story. Some have to be removed, but it takes time to discover which ones.

“I was looking at something growing in my garden the other day, and I wondered if it was a weed or not,” Kimberly says. “I’m not sure yet, but I’m going to wait and see.” Sometimes her writing ideas are that way too. She waits to see how they develop before she knows whether they will grow into something beautiful in her story.

Kimberly says she is fascinated by process in writing and loves it, even when it is a painstaking process. “I have to love it, because I have to rewrite so much. I can’t just feel mediocre about a story, because it won’t keep me writing through the whole process,” she says. “I get great ideas, but not all are my stories to write because I don’t care enough about them.”

Journaling is another tool she uses in her writing process. She keeps a separate journal for every book she writes, recording her thoughts about her work at the end of each day. These journals are not part of her manuscripts or rewriting, she emphasizes, but provide a separate place to work out problems, questions, or frustrations with a project, while staying connected to it.

“I can go to the book journal when I don’t want to go to the manuscript,” she explains. “I can whine and complain on paper, when I’m stuck, when I’m having trouble working out something in the plot.”

As with writing, she keeps a journal about gardening too. “I enjoy my journals, and I don’t judge my prose. It’s mainly about when I plant things. What are my dreams? A journal is such a helpful tool. You see your thought processes on the page.”

The processes of writing and tending her garden are naturally intertwined for Kimberly.

“With a book, you have to think about who will tell the story, who the characters are, the setting, the situation. Before you put pen to paper to start at the beginning, those are the things you have to think about, otherwise, the story will dry up, like if you just throw a bunch of seed out without preparing the soil. After you prepare the soil and plant the seed, then you’ve got to nurture it. Keep working at it every day. Tend it to be sure it has everything it needs to grow, and step away when you need to let it develop.”

Kimberly’s writing wisdom (more tips on her website):

- Turn off your inner editor while you’re the creator. Create freely first, edit later.

- Use a list to brainstorm or make notes about a place or event. It’s easier to write things we notice as lists. We don’t have to be lyrical. Just make a list of words. You can create strong prose later.

- Keep a journal as a place to work out writing problems, to see your thought processes on a page.

- Look at anthologies and read first sentences. That has helped me think about what makes a great first line for a story.

- When it comes to setting think small, not big. Don’t talk about the whole Texas panhandle at once. Where are you? In an abandoned church. That’s nailing it down.

Kimberly’s recommended books on writing:

- Writing on Both Sides of The Brain by Henriette Anne Klauser

- The Weekend Novelist by Robert J. Ray

- Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity by Ray Bradbury

- The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp

Kimberly Willis Holt

Web: KimberlyWillisHolt.com

Facebook: Kimberly Willis Holt and Blooming at the Texas Sunrise Motel

Pinterest: @MyJoyfulJourney

Instagram @kimberlywillisholt

Terri Barnes is a regular contributor to Books Make a Difference magazine, author of the book Spouse Calls: Messages From a Military Life, and senior editor at Elva Resa Publishing (a publisher specializing in books for and about military families). Terri’s husband is a retired Air Force chaplain.

This article was first published May 2018.

AThis is so interesting. I remember reading part of this before. Love this process.