Fifty-four years after they went to jail for sitting at a whites-only lunch counter in Rock Hill, South Carolina, the eight surviving members of the Friendship Nine are returning to court to have their convictions vacated. Their new day in court came in no small measure from a children’s book, No Fear For Freedom: The Story of the Friendship 9, and the efforts of its author, Kimberly Johnson.

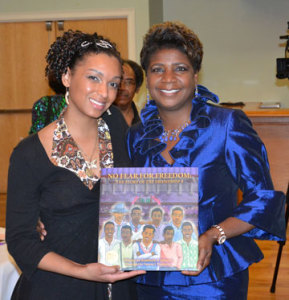

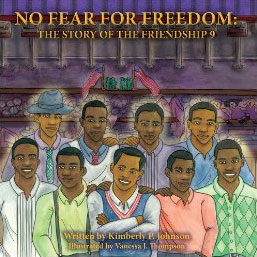

No Fear For Freedom, written by Kimberly Johnson (right) and illustrated by Vanessa Thompson, is designed to appeal to all ages. The main story is presented as a picture book for young children; historic details in the margins hold the interest of older children and adults.

The picture book, illustrated by Vanessa Thompson, depicts the history of a group of students from Friendship Junior College and their story in the Civil Rights Movement. After being arrested for a sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter in 1961, the men opted to stay in jail rather than pay bail, initiating the “jail, no bail” strategy and reinvigorating civil rights protests around America.

Kimberly first met Clarence Graham and other members of the Friendship Nine at a fiftieth anniversary celebration in Rock Hill in 2011. At that first meeting, Kimberly was embarrassed to admit that, even though she lived less than a half hour away from Rock Hill, she was unaware of the Friendship Nine story and its significance.

“When I was introduced to them, I told them ‘I’m so sorry I don’t know as much as I should about my own history. I’m going to read everything I can find about the Friendship Nine,’” Kimberly recalls. “Mr. Graham said, ‘There’s not a whole lot written about us.’ And I said, jokingly, ‘Well, I’ll read a children’s book, cause that’s more my level anyway.’ And he said, ‘Well, there certainly isn’t a children’s book.’ And that’s how the conversation started.”

As Kimberly began researching the story of the Friendship Nine, for her own education as well as to write a children’s story about it, she discovered that few South Carolina newspapers covered the event at the time. “They didn’t want people agitated about what was going on, so they didn’t run a whole lot of pictures or stories about the movement,” she says. “But a lot of the other Negro papers, like Baltimore, Chicago, Atlanta—they ran stories on the ‘Rock Hill Nine,’ which is what they were called initially, so I went to their archives.”

Most of her information, though, came directly from getting to know the surviving members of Friendship Nine in person over the past three years. “They are so cool,” she says. “They’re funny and smart. And they’re very committed to this chapter of their life. They want to send out a message that young people don’t have to act violently in order to get results. That’s what they represent. What they did back in 1961 was a very big part of the Civil Rights Movement.”

Sit-ins and protests, mainly by college students, had been going on at restaurants and bus stations throughout 1960, resulting in mass arrests. The protesters were fined 100 dollars or more each time they were arrested.

“The economic piece was destroying the community,” she explains. “[The activists] didn’t want to keep feeding into the same system that was stripping them of their rights.”

So when this group of students from Friendship College organized their Rock Hill protest, they decided ahead of time that, if arrested, they would serve jail time rather than pay bail. Their hope was to break the cycle of paying into an unfair legal system while bringing wider attention to public segregation.

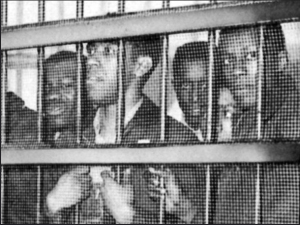

Members of Friendship Nine accepted a 30-day jail sentence at a prison farm rather than paying bail, initiating a “jail, no bail” strategy that changed the course of the Civil Rights Movement in America.

On January 31, 1961, they walked to McCrory’s lunch counter in downtown Rock Hill. Police were on duty as they had been notified ahead of time of the protest. Ten of the protesters sat down at the whites-only counter, asked for service, and refused to leave. Nine of the men were teenage students at Friendship Junior College: Willie McCleod, James Wells, Clarence Graham, David Williamson Jr., Robert McCullough, Mack Workman, W. T. “Dub” Massey, John Gaines, and Charles Taylor. Civil rights organizer Thomas Gaither was a field secretary for the Congress of Racial Equality who helped organize the protest and joined the young men at the counter. Eight of the students grew up in Rock Hill. Taylor was from New Jersey and was attending Friendship on an athletic scholarship.

All ten men were arrested and found guilty of trespassing the next day in court. Taylor was concerned about losing his scholarship, so he paid his bail with the help of the NAACP. The remaining nine refused to pay the 100 dollar fine, instead accepting a thirty-day jail sentence of hard labor at the York County prison farm.

Their efforts changed the direction of the Civil Rights Movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had been discussing what to do about the challenge of scarce bail money. While a jail stay required more commitment from protesters, the “jail, no bail” strategy reversed the financial burden, making white authorities pay for jail space and food rather than the protesters subsidizing a legal system that supported segregation and inequality. The character and impact of protests changed around the country.

Kimberly says, “These men were treated as criminals, but they’re not. What they did is really powerful and right. For these men to take that kind of a bold move was unheard of.” She, like many others, wants to see their criminal records reversed. But it wasn’t clear to her how the convictions could be changed while keeping the important record of what these men had accomplished.

In the summer of 2014, Kimberly accepted an invitation from Bernice King (daughter of Martin Luther King Jr. and CEO of the King Center) to attend the King Center’s weeklong N.O.W. (Nonviolence Opportunity Watch) Encounter summer camp.

Kimberly attended a nonviolence camp with Bernice King, who wrote the book’s foreword. At the camp, she reread “Letter from the Birmingham Jail,” which inspired her to talk with her local solicitor about using the unjust law argument to help the Friendship Nine.

“Ms. King is very committed to keeping her father’s work going,” says Kimberly. “At the camp, you study the philosophy and methodology of Dr. King.”

One part of her study was to reread Dr. King’s 1963 “Letter from the Birmingham Jail” about unjust laws. Though Kimberly had read the letter many times before, reading it after writing about the Rock Hill event gave her a new perspective.

“Dr. King said that people who didn’t follow the law at that time weren’t being disobedient to the law, they were being disobedient to the immorality of the law,” she says. “So when I started reading all that in the letter, I thought, this is just like the Friendship Nine. When I came back to Rock Hill, I talked with our circuit solicitor Kevin Brackett about it.”

Brackett was at first hesitant, concerned that “everyone would knock on his door to get their records cleared.” But he investigated the unjust law perspective and came back to her with the commitment: “that’s how we’re going to clear their names.”

So in January 2015, fifty-four years after they were arrested, the men will be back in court at the Moss Justice Center in York, SC. Brackett will make a motion to have the case vacated, under the argument that the law making it a crime for blacks to sit at the lunch counter was wrong and the men should never have been arrested and convicted in the first place. The court hearing will keep history intact while acknowledging the wrong done in the legal system. He says this action does not change the courage and valor of these great men who stood up against segregation, but legally, it will clear the unjust conviction. It will right a wrong, he says, while ensuring that what these men did will not be forgotten.

Kimberly points out “a bigger irony: the judge who sentenced them back in 1961—it’s his nephew who is going to hear the case.” The presiding judge, Circuit Court Judge John C. Hayes III of Rock Hill, is the nephew of the original trial judge, the late Rock Hill City Judge Billy Hayes. “That’s pretty wild,” she says.

Retired SC Chief Justice Ernest Finney, the defense lawyer who originally represented the Friendship Nine in 1961, will represent the eight surviving Friendship Nine members again. Finney was the first black person on South Carolina’s Supreme Court. He is eighty years old.

Several events will lead up to the court date, culminating in a full-length musical about the Friendship Nine, collaboratively written by Bruce McKagan and Kimberly, which she says plays out “their life, how it happened, how they decided to do the movement, and why they decided to do it.”

The official court date has been set for January 28. The musical will be performed on January 30 and 31. On January 31, the anniversary of the sit-in, the local police department will line the streets with police officers, just like they did in 1961. And the surviving members of Friendship Nine will walk across the street to the lunch counter as they did 54 years ago, but this time as welcome guests.

Kimberly and her husband, Jeff, reside in York, SC, near her hometown of Shelby and historic Rock Hill.

Kimberly says she never expected all the attention her book has garnered for the Friendship Nine. Her intent was simply to share a local story with others outside her community, but in an effort to help her new friends, she is making history by retelling it. Her storybook has garnered renewed interest in a key historical moment that celebrates courage and a different meaning of conviction. She hopes it will do more than right a wrong.

“[This experience] has made me realize that we don’t know enough about history. I don’t care what color you are—Black, White, Asian, Hispanic—we do not know enough about our culture. There are so many people who are local heroes who will live and die, and we will never know anything about them,” she says. “These men were ordinary people who did extraordinary things. They live right here in our community. When I first started writing this book, there were a lot of people in our community who didn’t know who the Friendship Nine were and they live here.”

Kimberly feels the greatest contribution anyone can make is to help children understand themselves through stories. “You cannot love yourself if you don’t know yourself,” she says. “How can we expect kids to act better or make better choices if they don’t know how powerful their histories and their legacies are? That’s what I learned the most, that as a community, as parents, we have to give our kids the history they need so they can understand who they are and the fiber from which they are made.”

She adds, “The biggest thing I’m walking away with is: know your history. Know who you are and where you come from. Because then you can keep these stories alive. There are a lot of greats in our history that our kids will never know if we don’t teach them.”

Kimberly Johnson:

Kimberly Johnson:

Web: www.SimplyCreativeWorks.com

Facebook: /SimplyCreativeWorks

Friendship Nine:

Web: www.Friendship9.org

Facebook: /FriendshipNine

Public television show produced by South Carolina ETV called “Jail, No Bail”: SCETV.org

Buy the book at Kimberly’s website, MilitaryFamilyBooks.com or Amazon.com.

All photos used with permission.

Inset photos courtesy of Kimberly Johnson, except jail photo courtesy of Friendship Nine.

Feature photo by T. Ortega Gaines (Charlotte Observer): Civil rights activist David Boone, left, who took part in 1960s sit-ins, and Friendship Nine members Clarence Graham, James Wells, Willie McCleod, and W.T. “Dub” Massey, meet with author Kimberly Johnson, second from right, at the former McCrory’s store, now the Five and Dine restaurant, in downtown Rock Hill, South Carolina.

The following excerpt from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from the Birmingham Jail,” inspired Kimberly to approach her county solicitor and ask him to vacate the Friendship Nine convictions: “…an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

Karen Pavlicin-Fragnito is an award-winning writer and publisher of Books Make a Difference magazine. She and her cousin Kim Johnson have enjoyed sharing their writing journeys with each other for many years. Contact Karen.

This article was first published in January 2015.

Kim call me PLEASE

MR GRAHM PASSED AWAY