A guide dog waits patiently for his blind master to situate the handle of the harness in one hand and his cane in the other so he can open the door for his guest. Tobi is Max Edelman’s third guide dog and the pair stands poised at the open door so Max can hold it open for journalist Sharon Peters. Manners matter to Max, no matter how much maneuvering it takes to present them. For the last four hours, Tobi has laid at Max’s feet while Max shared with Sharon stories about surviving the Holocaust, his life as a blind immigrant after World War II, and his eventual acceptance of a dog as his guide. They are taking a lunch break before they continue the emotional conversation. Max has shared with Sharon personal and unfathomable atrocities, including details he has not been able to enunciate at any other point in his life. Finally able to reveal the depth of his pain—the truth of his life at the hands of the Nazis—Max shares all of it with the only writer he has trusted enough to write the entire story—a long-time journalist and now pet columnist for USA Today.

Sharon found Max when she was doing preliminary research for a story about guide dogs for her weekly “Pet Talk” column. She had heard repeatedly about a Holocaust survivor who had taken on a guide dog despite the fact he was terrified of dogs. She thought the story was urban legend, until she heard it frequently enough she felt compelled to ascertain whether it was true. She eventually found Max, who had witnessed a German Shepherd maul to death a fellow prisoner in a labor camp during the Holocaust.

At age seventy, Max decided to push through his terror of dogs and began working with his first guide dog, Calvin. Calvin sensed Max’s hesitancy with him. In fact, initially, Calvin refused to work for Max because mutual trust did not exist. Max and Calvin struggled for months to have the relationship required for a service dog to perform. Sharon writes, “So they walked, Max inching toward confidence in Calvin’s dependability, and Calvin, Max assumed, inching his way toward whatever it was that he needed.” Over time, and an incident in which the dog reacted and saved Max being struck by a car, Calvin taught Max to trust him. Max developed confidence in Calvin and that translated into a deepening trust of people too, especially those who had become interested in his story. By the time Max met Sharon, many of his barriers had been broken down.

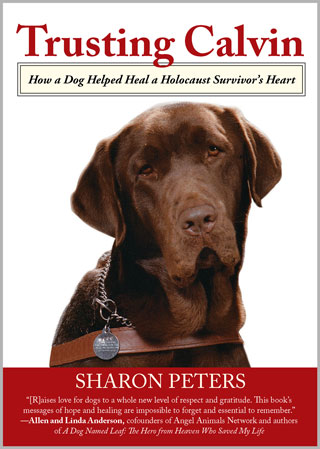

The resulting book, Trusting Calvin: How a Dog Helped Heal a Holocaust Survivor’s Heart, chronicles the incredible journey that put Calvin in Max’s life.

The resulting book, Trusting Calvin: How a Dog Helped Heal a Holocaust Survivor’s Heart, chronicles the incredible journey that put Calvin in Max’s life.

It is the story of a young Jewish man who endured five labor camps in nearly five years, including the last camp where he was beaten blind by guards. He evaded Nazi detection as a blind labor worker, was starved nearly to death, and yet found the stamina to march for seven days to the safety of an ally-controlled area. Before being blinded, Max had been destined for medical school; instead, he became a meticulous darkroom technician who processed x-ray film in order to support his family. It is the story of a man who spent his life terrified of dogs, and at age seventy asked to be trained to use a guide dog.

Sharon’s path as an animal lover turned pet columnist led her to Max. If it hadn’t been for Calvin’s role in the story, she would not have written the book. What began for Sharon as a story about Max’s leap of courage to work with Calvin, became the multi-layered story of a lifetime of courageous decisions. Max opened up to Sharon because she knew how important Calvin was to changing his life.

“Max was the biggest gift that happened for me in decades,” Sharon says. “To suddenly be presented with a man of such incredible honor and intelligence and for him to trust me enough to [write about] his life. It was amazing.”

As compelling as Max’s story is, it was the man’s late-life connection with Calvin and two subsequent guide dogs that prompted her to agree to write her first general interest book.

“I wouldn’t have had as much interest were it not for the fact that when he was seventy he had to have dogs in his life. It changed the last twenty years he lived.”

The only way a guide dog relationship works is through trust. Sharon’s understanding of the powerful possibility of relationship between dogs and people is one reason Max trusted her with his story. Max wanted to tell Calvin’s story too.

Sharon hadn’t always been a writer for and about animals. Prior to her work as a pet columnist at USA Today, Sharon had been a reporter or editor for several papers all over the country. She was the executive editor of the Colorado Springs Gazette newspaper when Hurricane Katrina hit. She felt compelled to take a one-month leave and travel to the storm-ravaged area and volunteer with the clean-up. While there, she spent her days volunteering at the animal shelter in Gulfport, Mississippi; at night, she hung drywall and cleared downed trees and wreckage. It changed her. She walked dogs during what would be their last minutes of their lives. With so many animals and so little space, hundreds of perfectly healthy animals were euthanized.

On her return to Colorado, Sharon wrote a couple of pieces about the plight of the animals, including her frustration that there was no program in place to get the animals transferred to other facilities. She continued to feel a pull to do something for the dogs who couldn’t speak up for themselves. After two more visits to Gulfport, she quit her job in Colorado Springs. A professional writer, she knew she needed a platform to tell the dogs’ stories, and possibly address other issues of animal health, rescue, and care. She approached editors she had previously worked with at USA Today and told them they needed to have a regular infusion of stories about pets. Within six months, she had a contract with USA Today to write at least two pet stories a month, and a few months later the paper launched her weekly “Pet Talk” column.

She wrote for those who could not write for themselves. By the time she was presented with a story about a man whose personal story was, for all intents and purposes, too hard for him to write himself, she was the perfect person to do it.

Forty-eight hours after her original article about Max and Calvin ran in USA Today, Sharon was contacted by an agent as well as two firms who represented publishing houses. All were asking for a book version of the story about Max.

“I’m just not a book writer,” Sharon replied. “I wouldn’t object to writing a book at this point, but I have a full time job. I can’t not work.”

She knew it would take her a year or so to write the book, and she was not in a position to put her paying job aside for a book-writing venture that could not ensure some income.

“I’d love to see his story told, though,” she told the agents, “so if someone else wants to write it, I’ll connect them with Max.” A couple of different writers tried interviewing Max, but, from Max’s perspective, they just did not work out.

Two years passed and nothing more came of Max’s story. Sharon was then contacted by another agent, Andrew Stuart, who emailed her, singing praises for her column and commenting, “you have a book in you.”

At first she again said no. “No book. I can’t stop working.”

After continued conversation she eventually conceded, “If I’m going to write a book, I am only going to write a book about Max Edelman.”

Collecting the memories of a Holocaust survivor is an arduous, time-consuming, and certainly emotional endeavor. Sharon knew much of this would have to be face to face, and she arranged to fly to Cleveland to conduct interviews with him there.

“Max and I would start taping at eight each morning and finish at six or seven at night,” she says. “I would go back to the hotel at night and I wouldn’t sleep. I’d show up the next morning and I’d say, ‘Max, I don’t feel terrific after no sleep. And I’m pretty sure you had a sleepless night, too, after dredging up all those memories. Do you just want to take today off?’”

“Max would reply, ‘Do you have any idea how old I am? I can’t put this off. We’ve got a job to do.’”

By the time Sharon interviewed him for the book, Max was in his late eighties and he knew time was limited. He had already told several parts of his Holocaust survivor story at speaking appearances and he had written other parts for various articles. For those shorter snippets of the story, Max had the luxury of being able to stop without going any deeper than he felt like he wanted to delve.

“When he was talking to me,” Sharon says, “he didn’t have that privilege. He was forced to go a lot deeper.”

She notes that Max was obviously discomforted at times, but he was all in for the completion of the project.

The relationship that grew between Sharon and Max went well beyond journalist and story subject. They became close friends and Sharon admits she became incredibly protective. Toward the end of Max’s life, he had significant health issues. The book had been published and there was starting to be increased interest for interviews with or appearances by Max.

One high school world history teacher from Minnesota tracked Sharon down to thank her for the book. The teacher was preparing to take a group of students to tour the labor camps in Germany and she was interested in Max’s experiences. She asked about setting up a phone interview with him.

Sharon presented the idea to Max, but reminded him he was under no obligation and, because of his failing health, it would be appropriate to tell the teacher no.

“’Could you stop?’ Max told me, ‘Just tell her to call me Saturday night at seven. Tell her ahead of time I may tell her I’ve had a bad day and have to hang up, but if I can talk, I will.’”

Sharon called the teacher back with Max’s agreement and warned her about Max’s frail condition. Sharon made it clear that the teacher should be on the phone no more than fifteen minutes.

Sharon says, “When you know what someone’s been through and is going through now healthwise, I couldn’t help but to think, ‘how can this man be so generous and courteous?’”

The teacher reported in the next day.

“’It was one of the best experiences of my life,’ she told me. ‘I promise I said thank you and I will let you go, at fifteen minutes, and again at thirty minutes and again when an hour had passed.’”

The story that Max wan unable to share for all those years was making a difference for people and he knew it. Because the woman was a teacher and she would be sharing Max’s story with classrooms of kids, he stayed on the phone with her for nearly two hours. He died seventeen days later.

Sharon Peters walked dogs in their last minutes of life after Katrina. She grieved that they would not be able to share their power and their magic with people, regular people, who could learn much about joy, living in the moment, and generosity of spirit. Guide dogs walked with Max the last twenty years of his life and it is because of those dogs, and his relationships with them, that Trusting Calvin was written and will inspire people for generations to come.

Sharon Peters on Goodreads.

Facebook: /AuthorSharonPeters

Meagan Frank is senior writer for Books Make a Difference and is working on her first novel. www.MeaganFrank.com

If you are interested in this topic, you might also like:

Holocaust Survivor/ Remembrance Organizations

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: www.USHMM.org, @HolocaustMuseum

Holocaust Center: www.HolocaustCenter.org, @HolocaustMI

FL Holocaust Museum: www.FLHolocaustMuseum.org, @FLHolocaustMus

Yad Vashem: www.YadVashem.org, @YadVashem

Holocaust Center: www.Hmtcli.org, @HolocaustTolCtr

VA Holocaust Museum : www.VaHolocaust.org, @VaHolocaust

Holocaust Education: www.ioe.ac.uk/Holocaust, @IOE_Holocaust

Vancouver Holocaust Centre: www.vhec.org, @VHolocaustCntr

Holocaust Center of Florida: www.Holocaustedu.org, @HolocaustCenter

Holocaust Studies US: @WhyTheHolocaust

Miami Holocaust: www.Holocaustmmb.org, @MiamiHolocaust

Tennessee Holocaust: www.TennesseeHolocaustCommission.org, @TNHolCom

Holocaust Education Resources: www.HolocaustEducationResources.com, @HolocaustEdRes

Holocaust Council of New Jersey: www.jfedgmw.org/Holocaust, @HolocaustGrMW

Anne Frank Center USA: www.AnneFrank.com, @AnneFrankCenter

Holocaust News: www.Enzel.org, @HolocaustNews

Cape Town Holocaust Center: www.Holocaust.org.za, @CTHoloCentre

Guide Dog/ Service Dog Organizations

Today Show’s Puppy with a Cause: www.Today.com, @WranglerTODAY

Guide Dogs UK: www.GuideDogs.org.uk, @guidedogs

Sponsor A Puppy: www.SponsorAPuppy.org.uk, @SponsorAPuppy

Southeastern Guide Dogs: www.GuideDogs.org, @SEGuideDogs

Guide Dogs NMT: www.GuideDogs.org.uk/Nottingham, @guidedogsNMT

Guiding Eyes: www.GuidingEyes.org, @GuidingEyes

Guide Dogs Western Australia: www.GuideDogsWA.com.au, Twitter: @GuideDogsWA

Guide Dogs of Texas: www.GuideDogsofTexas.org, Twitter: @BestDogsInSight

Guide Dogs NSW/ACT: www.GuideDogs.com.au, Twitter: @GuideDogsNSWACT

Guide Dogs Queensland: www.GuideDogsQld.com.au, @GuideDogsQld