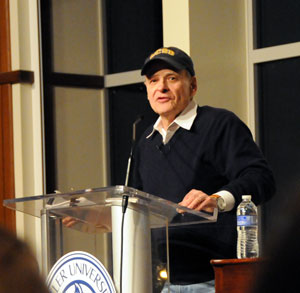

Looking out from beneath his ever-present baseball cap, Tim O’Brien opens his visiting authors’ speech with the humble disclaimer, “I have no real expertise except that which comes from living on this planet for 67 years… I’m just a writer who sits in his underwear, writing stories.”

He begins with a humorous story about his youngest son, Tad, peeing into the wire wastebasket in Tim’s home office, an incident that came about because, in Tad’s words, he has two heads (one that told him Dad was not going to like this, and the other that thought it would be fun). Even in this endearing parenting moment, it is clear that Tim’s memories of war are as much a part of the fabric of his life as his writing—and parenting. It doesn’t take long for the story to find a connection to Vietnam. During bedtime stories that night, Tim told his sons that he, too, had two heads once: one telling him to serve his country and the other considering the alternatives… The story is a segue. Soon, the master storyteller has his standing-room-only audience spellbound, transported to 1969.

With more than 3 million copies of his books sold, and a long list of accolades for his work, including the National Book Award, Dayton Literary Peace Prize/Richard C. Holbrooke Distinguished Achievement Award, and Pritzker Military Library Literature Award, Tim O’Brien is known for his thought-provoking stories that use the Vietnam War as a backdrop for exploring the bigger questions in life.

Arguably his most well-known book, The Things They Carried is assigned reading in many high school and college courses, and has become a touchstone for verisimilitude, a literary device blurring fiction and reality. To Tim, the “story truth” is often far more interesting and worthy of exploration than what factually happened. “As a fiction writer, I’m not limited by what happened,” he says. “I can also write about what almost happened, but did not. I can write about what could have happened, or what should have happened, but did not.”

“Stories have the power to help us understand where we’ve been and where we might be going in our lives,” says Tim. “Stories can help us see the world freshly in a way we’ve never seen it before. Stories can give us access to other people’s lives, and thereby access to our own lives.”

Tim’s voice has given expression to others who struggle to find words, especially war veterans. About six years ago, he received a letter from a 26-year-old elementary school teacher. “I want to tell you about my life as a little girl,” she wrote. From the time she was in elementary school, she knew there was a tension, a sadness in her house. Her dad would sit down at dinner and stare at his food and not talk. In high school, she found a box with relics of her father’s time in Vietnam. She didn’t know her father had been in Vietnam. Like many vets, he had fallen silent. At one point, her mother told her, “You know, I’ve never loved your father, I married him out of pity. How can you love someone who never talks to you?”

The girl was assigned The Things They Carried when she was a senior. When she finished reading it, she left it on the table, and her father picked it up and read it. It started a little conversation. “My parents are still together,” she wrote. “I don’t think they would be if that book hadn’t been on that table.”

The girl was assigned The Things They Carried when she was a senior. When she finished reading it, she left it on the table, and her father picked it up and read it. It started a little conversation. “My parents are still together,” she wrote. “I don’t think they would be if that book hadn’t been on that table.”

Tim explains that the girl’s father is not unusual in his response to war. “By and large, they fall silent,” he says. “How do you find language to express it, make others feel it the way you feel it? Words are inadequate, so you fall into silence. There’s a struggle to wrap words around it. Silence is so corrosive. For a long time, I fell silent.”

Although his war experience ignited Tim’s writing career (his first book, If I Die in a Combat Zone, was published in 1973), his love of books and desire to become a writer were firmly planted in his childhood. His dad was a member of the library board and his mom was also an avid reader. “I grew up in a house full of books,” he says. “There were books everywhere—the bookshelves, coffee tables, bedstands. I would pick them up and read for as long as I was interested. I doubt I would have been a writer without the physical presence of books in the house.”

One impactful childhood memory stands out for Tim: “One of my earliest literary memories is of my father reading a book in the living room. It was winter in Minnesota, twilight hour. There was a light on behind him. I walked into the living room and saw this look on his face I’d never seen at the dinner table. It was a look of peace, delight, and contentment. Total absorption in whatever he was reading. I remember looking at his face and wishing I could be that book, so that he would look at me with that same happiness, delight, and contentment. I didn’t get that from him. He was a silent and brooding man, a bad alcoholic. Things were always tense around the house. So it had nothing to do with the words in the book. It had to do with books, period. Something happened to him as he was reading that book—he looked happy to me, he looked somehow renewed and revitalized and at peace with himself.”

Becoming a dad himself has also changed Tim’s view of the world—and his writing. Although Vietnam still invades his stories, even those he tells his boys, he now sees life through soccer games, magic shows, and a tree house window.

Tim celebrates with sons Timmy and Tad at the Dayton Literary Peace Prize celebration in 2012. Tim considers this lifetime achievement award to be among his highest honors. Its objective is “to advance peace through literature.” For decades, Tim has signed his books, “Peace, Tim O’Brien.”

“I didn’t want children,” Tim says, “I thought they would get in the way of the important stuff of life. I didn’t realize they are the important stuff of life.”

Timmy, 10, and Tad, 8, are the eager listeners of their dad’s bedtime stories.

“The stories are pretty gross,” Tim admits. “Full of potty humor. I try to give some meaning to it all in the midst of the humor. I try to keep the stories attuned to what they’re going through in their lives. Sometimes, once every tenth story, they end up being extremely cool stories. I’ll tell it to my wife the next day and she’s keeping a log of the good ones. The ones that have some staying power, she’s written down. What we’re going to do with them, I have no idea.”

Tim is more than half way through his current writing project. “It’s been a long, hard chore, mainly because of the kids,” he shares. “You have to give kids what they deserve, which is your time. Before having kids, I was completely selfish. Time was mine and I wrote day and night. Even though the book is about being an older dad—that’s the content of the book—it’s been hard to write because I am a dad. It’s hard to find the sustained time to do it. But the results so far, I’m really happy with. It’s not a hallmark card, it’s not schmaltzy. I think it’s really good. But you don’t really know until a book comes out—and then you don’t know for fifty years or more afterward if a book will endure or if it will continue to touch people. I do know I’m having fun writing it.”

A self-proclaimed slow, painstaking writer, Tim says, “I’m often dissatisfied with my own prose. That’s why it’s taken so long to write each of my books.”

He revises his stories even after they are published. For the twentieth anniversary edition of The Things They Carried, Tim revised many pages. “The stories themselves don’t change,” he says. “But the storytelling language often does need tweaking—sometimes just a word or two, sometimes a bit of punctuation, sometimes whole sentences. Most often, I find myself fiddling with little writerly things. Unintentional repetition of certain words. I doubt many readers would notice, but I do. You know you can’t make anything perfect in this world, but you can at least try your best to approach perfection, even knowing you won’t achieve it. My desire is to leave behind a kind of gift for the human race, a gift that is as beautiful as I’m able to make it. That’s my goal. If that means I’ll do more revisions in ten years, I will.”

Tim talks with Karen at The Efroymson Center for Creative Writing, his temporary apartment for the visiting authors’ series at Butler University. Finally capturing a moment to relax after a long day of lectures and discussions, the storyteller shares how becoming a dad has changed his view of the world—and his writing.

For Tim, his stories, his characters, are in many ways like his own children. “The product of forty years is really eight books, six of which are good. I’m not sure Warren Buffett would say that’s a decent return on investment,” Tim says. “But they are like children. I love some of my books. I think Tomcat in Love is a terrific book. I think it’ll endure. I think it’s smart and funny and properly bellicose, and I like that book in the same way I might like an errant kid. There’s a personal attachment to it that’s not completely literary. My affection for Tomcat in Love has to do with the book’s humor, which appeals to my pretty eccentric funny bone, but which may not appeal to the funny bone of someone else. That’s utterly out of my control. For me, Tomcat in Love has a storytelling voice that’s utterly foreign to my own—the voice belongs to the main character, a bizarre and sometimes revolting man, but revolting in a funny way. In one sense, it feels as if a character of my own creation suddenly hijacked my novel and began writing it himself, elbowing me out of his way. Yet, at the same time, I did slave over that book, every syllable, every comma, every bit of dialogue and narration.”

It’s that line by line labor that Tim says he takes the most pleasure in as a writer. “I do know when a note is hit and when a line is going to endure,” he says. “That’s the payoff—the language in the books. When I read somebody else’s book and I feel a rush of adrenaline and happiness over a line or a scene, it makes me happy for the writer and happy for the universe that that line exists in the world.”

He adds, “I uttered a line tonight in that talk. I said it at the end of the story about the little girl: Surely, the world is now a better place. [When I said that line] I stopped and looked at the audience. That’s what wars are supposedly for. We don’t go to war for fun. We go to war to make the world a better place. And there’s this dead little girl. So surely, we now live in a better world. But, of course, it’s pure irony, because we don’t live in a better world, because dead little girls don’t make the world a better place, and because all our wonderful reasons for going to war are always subverted and dwarfed by the horrors of war itself.

“I’m going to use that line somewhere. It’s not a fancy line. In its own right, it’s almost meaningless. But when it’s attached to a dead little girl, it’s a stopper. The language stops it.

“That image had been with me for years and years, that dead little girl. It’s a real image, on a real day in Vietnam. But I never used the image or that memory, because I never found the language to attach to it. There are a million dead kids in war, a million open wounds and shot off faces. They’re a dime a dozen. It’s the attachment of a bit of language that puts an edge on it and transforms it into something new and startling. Surely, the world is now a better place.”

—-

Feature photo: The O’Brien family: Tim, Tad, Timmy, and Meredith. Family life is Tim’s greatest joy. Tim and Meredith happily participate in imaginative adventures with their boys. Calling his sons “the important stuff of life,” Tim says, “You have to give kids what they deserve, which is your time.” Photo courtesy of Tim O’Brien.

Inset photo 1 by Karen Pavlicin-Fragnito. Inset photo 2 courtesy of Tim O’Brien. Inset photo 3 by Geno Fragnito.

Books by Tim O’Brien:

If I Die in a Combat Zone: Box Me Up and Ship Me Home

Northern Lights

Going After Cacciato

The Nuclear Age

The Things They Carried

In the Lake of the Woods

Tomcat in Love

July, July

Karen Pavlicin-Fragnito is a freelance writer and publisher of Books Make a Difference. Early in her writing career, Karen received a gift from a friend—a copy of The Things They Carried—as an example of exceptional writing to emulate. Contact Karen.

This article was first published in May 2014.

Karen, Thanks for sharing this wonderful story about Tim O’Brien and his writing life. It inspired me!