In July 2018, Books Make a Difference magazine, in partnership with Writeaways and Elva Resa Publishing, announced the award of a full scholarship to JT (Jenn) Blatty to participate in an October 2018 Tuscany Writeaway. The scholarship covered travel, tuition, and room and board at the villa. The magazine’s publisher, Karen Pavlicin-Fragnito, also attended as one of seven writers in the workshop led by Mimi Herman and John Yewell. Read a pre-Writeaway interview with JT and a recap of our social media coverage in the Writeaway section of the magazine. In this January 2019 feature, JT shares how the Writeaway made a difference for her as a writer.

When I was ten years old, my father gave me my first journal. Each page was like a portal into a new world that had previously only lived inside my mind.

Throughout grade school, high school, and my four years at the United States Military Academy at West Point, I wrote. As the writing matured, so did the facades of the notebooks—from a kitten and butterfly cover, to a spiraled book of psychedelic “Dazed and Confused” colors, to plain notebooks collaged with bottle caps and stickers from teenage adventures. And then, just months after 9/11, my journal changed form again—to a standard black bound book, handed to me as a gift on the day I departed for Kandahar, Afghanistan, with the US Army.

That’s when the content of my writing dramatically changed as well. I began to explore my experience as a 23-year-old platoon leader on the ground with the first troops into Afghanistan. One day, my journal entry became a handwritten “Chapter One” of a book I was determined to write, and the pages turned at a pace my hands would never be able to match today. I wrote about what it was like in a warzone, how we made it through each day, about fear and humanity and leadership and what defined the true meaning of patriotism. I wrote about what it felt like to finally reach that untouchable day of getting onto the aircraft that would bring us home. And then again, not long after returning home from Afghanistan, the pages resumed turning, when I deployed to Iraq with the first troops in 2003.

But the book, like my life, had an open ending.

When I arrived to the Tuscany Writeaway eight years later, I brought with me a hundred or so pages of stories and chapters, written and rewritten, and then written and rewritten again. Amidst the chaos of everyday post-Army life, working as a photojournalist and consumed by all the distractions of a first-world country, my writing had become fragmented.

The issue ran far deeper than distraction or a struggle with structure. I was conflicted with the protagonist, with the repeated “I” that made my nonfiction story feel like an egocentric memoir. This wasn’t just a story about me—it was the shared sentiments among my comrades, the stories of war and deployment and what we experienced together. It was, and is, about all of us.

Just before the start of the Writeaway, I was on a photo assignment in Ukraine and ended up spending a month embedded with Ukraine’s military community, interviewing volunteer soldiers in Kyiv. I literally boarded a flight to Florence from a warzone. I was in such a whirlwind of thought and emotion, I almost forgot my previous anxieties about the workshop: How would I be able to move forward on the manuscript in just one week? How could Mimi and John help me without reading what I’d already written?

On the first day of the Tuscany workshop, I met six other established writers—the kind of writers I envied, the kind who actually finished books (and some who actually had to decide which book they wanted to finish first). The instructions from John and Mimi were clear: write something new every day and be prepared to read the piece the following day during workshop hours, a time for constructive critique and feedback.

Something new. That meant no more writing and rewriting those one hundred pages of manuscript.

“Just start with a fresh page and write,” Karen calmly said to me on the side, sensing how torn I was over abandoning the manuscript. Ever since receiving the phone call from her during the summer, telling me I was the scholarship winner, I had envisioned these seven days to be the solution to my perilous journey, a breakthrough to finally move forward. I started with a fresh page and let the first scene that came into my mind fall onto paper in words.

Valkyrie. Her war name. The Russian traitor who fled to fight for the Ukrainian Army. In a flat in Kyiv, I stand around a folded-out coffee table in too small a kitchen where somehow we’ve all found a place to raise a variety of Airbnb-provided cups that we’ve repurposed into shot glasses. I watch her stand on a chair and the youthful brouhaha of the room grows quiet as she begins to speak in Russian to the Ukrainians, but they understand. Because after all, Russian is their first language.

I don’t speak either language, but I can feel the words of solidarity before she pours half her glass of whiskey to the floor by my feet. The others follow her lead, including me, because I know what they are doing: honoring the fallen. We’ve done it many other times, in different flats I’ve booked throughout the city over the course of a month, where these soldiers and veterans of the war, now in its fifth year in eastern Ukraine, have come together to congregate, to celebrate, to remember and to forget, and to tell war stories among comrades and even myself, a veteran of two other wars, from an Army in a country so far removed from their reality.

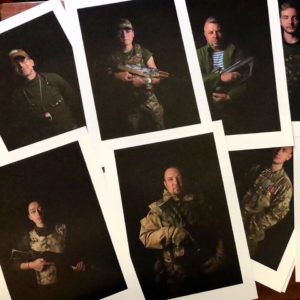

Earlier in the year, I had started a photo project in Ukraine, working with soldiers and veterans of the war in the Donbas, a topic that resonated strongly with my past. The volunteer soldiers there redefine the true meaning of patriotism. These ordinary citizens rose up of their own free will and took arms to save their country without obligation to the government, and many without military training, and self-deployed into a warzone to save their country against Russian-backed insurgents.

As I started to write deeper into the scenes of my time with these soldiers, I realized it was not going to be enough for me to simply photograph them. There was something within the journey that couldn’t be shown visually, and it was scratching at my gut to write about it. Ukraine was fresh, and it flooded my mind and heart.

During the next workshop, questions flowed from the other writers about the piece, about my place within the story, about my background and my life. Why did I feel compelled to go to Ukraine? How did I get this assignment? What made this project so meaningful to me? … They were questions I struggled to answer because they pulled me back into that same conflict of my manuscript’s narrative arc: It was too much about me.

I recalled something my Dad often told me, that writing is the most tortuous, painful, and isolating career to pursue. “I hate writing,” he’d often grunt from his giant office chair as he sat in front of his computer, rewriting every sentence, literally using his two index fingers while staring down at the keyboard (yes, he wrote novels like this). And he didn’t have to explain why, because I was just like him, too withdrawn in my own thinking, unable to see things from the outside.

At the Writeaway, I had to step outside myself and trust the encouragement of this community of writers who were quickly becoming friends. I had to trust that these questions they asked about me were of value to the story.

How did I get there? Before 2018, my knowledge of Ukraine was limited to a vague memory of Russians in Crimea and a commercial airliner shot down over a conflict zone near Russia. Only a 20-year losing streak of the United States Military Academy’s football team to the Naval Academy, the symbolic Army-Navy game, would by chance bring me into their world. Somehow the West Point’s local alumni organization got a hold of my email after I’d successfully dodged them and their annual events for years. I was finished with the Army, with the “system,” and I especially didn’t care to small talk with stiff, retired West Pointer generals and colonels about what I’d been doing with my life since getting out of the Army—that I was a freelance photographer, a writer, some kind of artist. Nothing could measure up to the work I was doing before becoming a so-called “civilian,” no matter how hard I tried. …

The only place I felt somewhat connected was due south, down the road, in the bayous of southeast Louisiana, where for over five years I often escaped to work on my project, Fish Town, a photo documentary of Louisiana’s vanishing fishing communities. But it wasn’t just about the project, it was about escaping the ins and outs of everyday life, the phone calls, the paperwork, the people of a fast paced, modernized and disconnected world where I felt more and more misunderstood with each year separating me from my end-of-service date. Down the road, there was simplicity: no cell phone reception, camaraderie, hard-working people. Sitting on a shrimp boat out in the middle of the Gulf with the guys, it almost reminded me of down time back in Afghanistan or Iraq, throwing rocks into tin cans and just being alive. …

I recognized a former classmate at the game. I remembered Dylan from the classroom, English 201 to be specific, the only semi-creative class included in West Point’s curriculum, and a vague memory of him standing to read some kind of beautiful, intense poem he had written for homework. …

What I’d learned about Dylan since running into him that day was how much he’d accomplished since getting out of the Army, and not in a corporate, bullet-on-a-career-resume type of way. He literally built an entire neighborhood from the ground up in eastern New Orleans, something he titled an “intentional community” for returning veterans of our wars. And I guess this wasn’t a big enough accomplishment for him, because next on his to-do list was a trip back to Iraq, to lay down the roots for a potential project that would help in the healing process of his former translator’s village that was destroyed.

I wanted in. He knew it and welcomed me. Because he knew that I was also searching for something, something that took me far too much time to understand. I asked him when we were going back to Iraq.

“After we go to Ukraine,” he said.

“Ukraine? What’s in Ukraine?”

“The war in the Donbas with Russia.”

War. Conflict. Soldiers. Veterans. It was all familiar ground. I needed it, because nothing seemed to fill the void I was trying to fill, this void that took me ten years to realize was connected to the same place I was always trying to escape. And now Dylan, the poet, the healer, the man of “intentional communities,” he was trying to bring me back into that world. …

Over the course of the week at the Writeaway, I wrote about my life, my search for purpose, the soldiers in the Ukraine. As I sat around the table or the living room in a villa in Tuscany, with John and Mimi, an overfed cat, and my fellow writers, something brilliant happened: I found the breakthrough I was looking for. In this space, where there was nothing to do except write and reflect, talk and listen to other writers, and eat far too much good food, I was finally able to clarify my purpose as a writer and a photographer and a veteran. The answers were present all along, in the one hundred pages of disorganized manuscript I originally brought to the table, and now, they were naturally falling into place as I wrote about Ukraine, as I wrote about these soldiers and my experience falling into place with them.

JT has spent months embedded in Ukraine’s warzone, interviewing and photographing volunteer soldiers for her documentary about the war in the Donbas. Photos by JT Blatty.

In late November 2018, for the first time in Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union, wartime status and martial law was declared in Ukraine. But there are soldiers who have been fighting a war in eastern Ukraine for five years. As a photojournalist and war veteran, I’m committed to telling their stories. Through my photos and writing, I will honor these soldiers and bring attention to this ongoing and forgotten war in a country teetering on the edge of democratic collapse.

Ukraine wasn’t meant to be the ending chapter. Ukraine is the new Chapter One.

Throughout the Writeway, John and Mimi and the other writers talked with each other about goals for their projects. One suggestion presented to JT was to pursue interest from national magazines. Following the Writeaway, JT showed her photos of Ukraine volunteer soldiers at PhotoNOLA, New Orleans’ Annual Festival of Photography, and pitched her story to several publications, receiving enthusiastic interest. If you are an editor reading this and you are interested in JT’s articles, photos, or manuscript, please contact JT directly.

Web: JTBlatty.com

Facebook: /JTBlatty

Twitter: @JTBlatty

Instagram: @JTBlatty

This article was first published January 2019.

Fabulous piece, JT. I loved being with you in Tuscany! Your writing is wonderful.