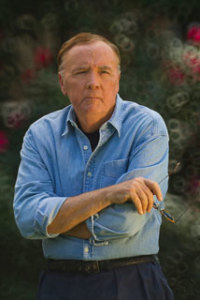

In Forbes magazine, he’s listed as the wealthiest author in the world. He’s in the Guinness Book of World Records as the author with the most books on The New York Times Best-Sellers List. With 128 titles in print, James Patterson has written thousands of sentences.

In Forbes magazine, he’s listed as the wealthiest author in the world. He’s in the Guinness Book of World Records as the author with the most books on The New York Times Best-Sellers List. With 128 titles in print, James Patterson has written thousands of sentences.

Perhaps the most surprising is this one: “I don’t wanna grow up. I’m a Toys R Us Kid.”

Yes, before he wrote dialog for crime-solving heroes like Alex Cross, Michael Bennett, and members of The Women’s Murder Club, James was a successful advertising writer and executive, putting words in the mouths of ad icons like the Burger King and the Toys R Us spokes-giraffe, Geoffrey.

Now with a powerful brand name of his own, James uses his advertising expertise as an author, taking an active part alongside his publisher in promoting his staggering numbers of books. He says he owes his literary output—at least in part—to skills honed in advertising, enabling him to keep up with a large number of story lines and characters.

“I’m sitting here at my desk now, going down the shelves,” James says from his estate in Palm Beach, Florida. “There are forty-some manuscripts here that are all alive. I don’t have any problem keeping them straight. When I was in advertising, I had a number of people working for me and hundreds of projects, and you kind of had to keep them all in your head.”

Collaboration is another tool borrowed from his advertising days, and one that causes some discomfort in the traditional literary world. James is unruffled by criticism of his successful formula—strategic use of co-writers—pointing out that many artistic endeavors are collaborative.

“People don’t think about how many collaborations there are,” he says, reeling off a list of creative teams, including Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lennon and McCartney, and Simon and Garfunkel. Add to that: Patterson and anyone. His name is that powerful, and he prefers to not work alone.

“On most television shows, it’s a team. On a lot of movies, there’s a lot of collaboration. People are like ‘Oh, my God. How could you do that?’ But people do forty-page television scripts with two writers. I don’t know how many I write. Five thousand pages a year or something. Last year, I did a thousand pages of outlines.”

All James’s books begin with detailed outlines, in which he lays out the plot in 70 or 80 handwritten pages. He then works with a co-writer who fleshes out the story and gets joint credit on the book cover. Patterson says his co-writers are true contributors to the story.

“I want their ideas,” he says, “and I want them to be invested in the project. I find that I wouldn’t be able to do what I do without help.”

James says most of his collaborators are people he knew from his advertising days. Others are people he met through their work or through friends.

Far from being a solitary writer, working in serene isolation, James enjoys sharing the creative process. He also seems glad to talk about his writing success and process, but he becomes much more animated when talking about literacy, books, and the difference they make.

It’s not just talk. As well as making millions of dollars, James also gives considerable amounts, in both dollars and books for programs to promote reading.

James Patterson talks with staff at Oblong Books in Millerton, NY, the first indie bookstore he visited after announcing he would donate $1 million to help bookstores stay in business.

He maintains a website designed to encourage children to read, ReadKiddoRead.com. He’s given hundreds of thousands of his own books to deployed service members and injured veterans. He supports multiple teacher education scholarships at more than twenty universities. In 2014, he gave $1 million of his own money in grants to independent bookstores, and plans to give more. That’s not an economic issue to him. He says what affects bookstores affects publishers and their ability to invest in new writers.

“What’s in jeopardy here is American literature, both fiction and nonfiction,” he says. “That’s a part of who we are and how we think, and the imprint we’re making on the world.

“It’s really important that we have really good bookstores. When [online retailers] are selling books at a loss, a small bookstore can’t do that. A lot of stores went out of business, and publishers are really getting squeezed. It’s getting harder for them to give advances for nonfiction that takes two, three, four years to write.”

James is concerned about writers and even more so about readers, particularly young ones. He’s emphatic about his efforts to encourage young people to read, relating his efforts with his own son, Jack, now sixteen.

“When Jack was eight, we said, ‘Jack, this summer you’re gonna read every day. You don’t have to mow the lawn, but you do have to read—unless you want to live in the garage,” James remembers. “We did our homework, and we got him about a dozen books, and by the end of the summer, he really enjoyed all of them.”

Getting children to read is important, he says, because it’s the way they learn about the world, its problems, and the need for finding solutions.

“If they don’t have a breadth of reading … they’re going to be so limited in terms of the way they see the world and what they’re capable of doing, and how their imaginations flourish,” he says. “People lecture kids, but teachers know stories have power.”

His emphasis on younger readers carries over into his own work. In addition to adult thrillers, James now has several series for teens and tweens that he calls “the most important thing I do.”

His series for middle-schoolers and teens include fantasy and realism, from Maximum Ride, about kids who are pretty normal, except they’re part bird, to Treasure Hunters, “about kids who are looking for real treasures around the world,” and I Funny, “about a kid who wants to become a great comedian, but he can’t be a standup comedian because he’s in a wheelchair. It’s about the role of humor in getting us through hard times.”

James’s reading material as a child was dominated by comic books and The Hardy Boys, but he grew up with more sophisticated tastes. Ulysses by James Joyce is one of his favorite works, simply because “It’s very difficult.”

His current reading includes both adult and kids books, of which his recent favorites are The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by Brian Selznik, and Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, which he calls “spectacular.”

A writer, philanthropist, and reader, James has many literary endeavors, but he balks at the “literary” adjective.

“Ah, yeah, literary? Well, it’s reading, especially with kids. Getting kids reading is for me a bit of an obsession, and we’re trying to do that.”

When writing for young readers, James says he doesn’t find it a stretch at all to see the world through their eyes and to write from that perspective.

“I’m a little surprised that people lose touch with what they were like as kids. I don’t find kids that much different today,” he says.

“I was fifteen. I was ten. It’s all very alive for me. I’m very much in touch with what it was like to be a kid,” says the author who penned, “I don’t wanna grow up.”

Web: JamesPatterson.com and ReadKiddoRead.com

Latest thriller: Hope to Die (released Nov 2014)

Twitter: @JP_Books

Facebook: /JamesPatterson

Photos courtesy James Patterson. Author portrait by David Burnett.

Terri Barnes is a military wife, and mother of three. She’s a newspaper columnist, and the author of two books: Spouse Calls: Messages From a Military Life and Stories Around the Table: Laughter, Wisdom, and Strength in Military Life. Connect with Terri on Facebook and Twitter.

This article was first published January 2015.