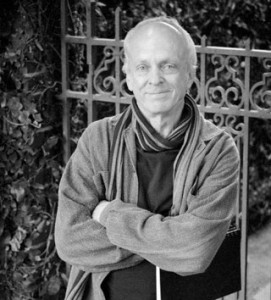

It is late afternoon on a chilly Tuesday. David Small and Sarah Stewart have gathered in the parlor of their historic home on the river in a small Michigan village. They laugh as they talk about books, life, and what it’s like to be married to an intensely creative person.

He is the self-proclaimed skeptic from Detroit who draws Caldecott-winning picture books and self-portrait errand love notes to his wife. She speaks in poetry, hand writes letters, reads Cassell’s Latin Dictionary every morning, and writes stories with profound simplicity and depth. Their multiple-award-winning creations come from a place that spans broken childhoods and a happy 32-year marriage. Books have mended them and given them each a voice to inspire others.

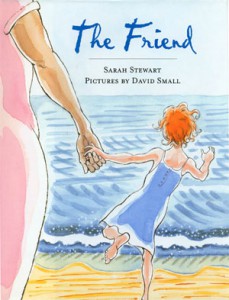

Sarah’s dedication in THE FRIEND reads: “To all the people across the world who have saved the lives of children by paying attention when others did not—but especially to Ola Beatrice Smith.” Sarah writes for people in her life.

Books and book-people began making a difference in their lives at an early age. Sarah shares, “I lived in one of those glass-globes-on-a-base, which, when shaken, makes snow or chaos of some kind, then settles down to order, even to beauty. Only, the globe I lived in was always being shaken. My father was often absent, away on business or fishing or hunting trips. My mother was a brilliant, powerful, raging alcoholic. The black woman, Ola Beatrice Smith, from whom I took most of the values I hold dear, ran our household. She and I went to the library every week on Saturday, beginning around my fifth birthday. There I found silence, order, and acceptance. The books were my instant, and only, friends. The librarians loved us, took care of us. Ola Bea had to touch me to remind me the doors were closing. Spending the night in my library would have been sheer bliss as a child.”

An artist who favors fiction by Chekov and Flaubert, David’s love of reading grew from teen defiance. “[When I was] thirteen, a school friend of mine–an avid reader whose parents let him read whatever interested him– gave me a paperback copy of Orwell’s 1984,” says David. “He pitched it to me as an amazing book about a future society gone wrong. I had barely begun reading it, when, because the book had one of those lurid ‘50’s dime-store jacket illustrations on it, my mother snatched it away and told me I could not be a friend with that boy anymore. Of course, this made 1984 the one single solitary book I needed to read as soon as possible. I stole a copy off the rack at the local drugstore, read it in secret, and followed it up with Brave New World. My reading, back then, was an act of rebellion, and I have my mother to thank for making me into the reader I am today.”

Creating their own books has been at least as important a journey. Sarah says, “The inscription I write in The Journey is, ‘The most important journey is inside yourself.’” She and David know this inner journey well.

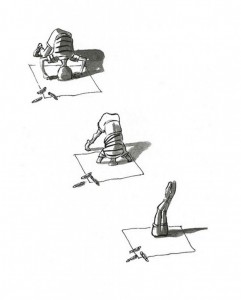

In his memoir, Stitches, David is a child drawing on a piece of paper on the floor. He burrows his head through his art into the world he drew to escape the world he lived in.

David says, “I think we all need escapes from reality. My escape has been through drawing.”

In addition to his picture books, David is known for his critically-acclaimed graphic novel memoir, Stitches. When David was 14, he lost his voice in an operation to remove the cancer that grew from his father performing experimental radiology on him. Illustrating his memoir was in itself a healing process for David. He explains, “Stitches was a book I had to make in order to find out why, after a half-century of life, I was still occasionally acting-out like a troubled boy of 14. By bringing everything and everyone back to life –by conjuring them up on the page– I was able to see objectively that, yes, I really did have an abnormal childhood. Afterward, it was –as a friend said–as if I had had shadow-removal surgery. There was, in other words, a transformation that the people closest to me could see and I can feel.”

David had previously illustrated several children’s books. The graphic novel was a new format for him. “I think I can say [the format] chose me,” he says. “I didn’t want to do a graphic novel. But, once I began drawing it out this became the perfect medium for me and for that book. My book is about being voiceless. I found that the graphic avenue allowed me to expand my story and to play with time in ways that are not possible in picture books.” (David eventually regained most of his voice by practicing yelling.)

Format has been important for Sarah as well. A writer who does not use a computer at all and only uses a typewriter when she’s sure she has something to say to someone other than herself, Sarah chose letters as a form of intimate storytelling in her books The Gardener and The Quiet Place. “Letters are just right for my characters, Lydia Grace, and Isabel, both, writing to beloved older women just like I used to write to Ola Bea,” says Sarah.

Sarah’s most valued award, which she won for The Gardener, was The Christopher Award, given to works that “affirm the highest values of the human spirit.” The award committee looks for creatives who celebrate the humanity of people in a positive way and remind audiences of their power to make a difference and positively impact and shape our world. Sarah says, “My story was, for their committee, the work of art that lifts the human spirit. I couldn’t imagine anything greater. It lifted me up. Of all the awards, that was huge.”

Her books and perspective have had a profound influence on others, beginning with her husband. David’s relationships, especially with Sarah, have in turn influenced his work. “I didn’t begin my work in picture books until my marriage to Sarah Stewart,” says David. “Those 30+ years have acted also on me as a form of shadow-removal surgery. Sarah’s point of view–so totally opposite to the cynical/pessimistic attitude I carried with me from childhood– and the stories she has written, have let me see life through a different pair of eyes and opened up a new world to me.”

He adds, “I used to think it would harm me in some way to be more sanguine about life, as if it was being untruthful. But when I committed myself to illustrating Sarah’s books, I found I benefitted from taking another viewpoint, in letting go of a bit of my disenchantment and distrust. I’m still a deep skeptic, but not to the degree I was before. And, that said, Sarah seems to trust me to bring out something necessary and unaccounted for in her stories, something that she would have been hard-put to allow there on her own. It’s an interesting blending of outlooks.”

David and Sarah will be married 33 years in September and have known each other 40 years. They knew when they met, “There was something huge between us,” says Sarah. “We have something between us that’s not understood by either one of us.”

Their love for each other is obvious to anyone who meets them. They both understand what it means to be married to someone intensely creative. David explains, “A couple months into our marriage, I said, ‘I need to be by myself for tremendous amounts of time every day.’ And Sarah put down what she was doing and said, ‘I need the same thing! That’ll be easy.’ What a relief.”

For Sarah, “It’s all about openness and forgiveness. A lot of young people don’t realize that’s the work of marriage. Openness to the other. And then forgiveness. Forgiveness and laughter.”

The two write and illustrate separately, following a traditional non-collaborative professional model. Yet their art is very much a part of their lives with each other and one of the things they appreciate most. “Sarah has a tremendous way with language. And a kind of perceptiveness with people I really admire,” says David.

Sarah refers to David’s art as marvelous, exquisite, magic exploding, even in the every day. “I live with a man who draws every day and I never know what he’s going to make,” she says. Even when David is just leaving the house and doesn’t want to disturb her, he draws. “Instead of interrupting me or just writing a note to say he’s running an errand or taking a nap, he draws a little picture of where he’s going and draws himself in it and what he’s going to do,” Sarah shares. “I have his tiny little work of art. And when we’re out, his eyes, because they are the eyes of an artist, his eyes see something I would never have noticed. I lead a much richer life because of David Small.”

Sarah refers to David’s art as marvelous, exquisite, magic exploding, even in the every day. “I live with a man who draws every day and I never know what he’s going to make,” she says. Even when David is just leaving the house and doesn’t want to disturb her, he draws. “Instead of interrupting me or just writing a note to say he’s running an errand or taking a nap, he draws a little picture of where he’s going and draws himself in it and what he’s going to do,” Sarah shares. “I have his tiny little work of art. And when we’re out, his eyes, because they are the eyes of an artist, his eyes see something I would never have noticed. I lead a much richer life because of David Small.”

Both David and Sarah are deliberate in the difference they hope to make for others through their stories. “I can’t help because of who I am to put more into them than what is on the surface,” says David. “That’s I think what pictures do, they get past all the guard towers and go straight to the heart in a way language doesn’t.”

Sarah believes each word should be carefully chosen. “Every word should be a world,” she says. “Very much like great poetry. I tell my students: don’t put it down on the page for the child learning the language to not have some great pleasure in moving across that line of words and sounding them out. I find such possibility for good in that, for joy in moving across a line of beautiful words.”

Above all, she believes in the power of a book’s unspoken message. “I’m trying to say over and over again that it’s okay to be a little outside the center of things. I’m not saying it deliberately, but in the undertow. It’s alright to be the outsider, to stand alone in the world and not be afraid to be alone. I was alone in my childhood. And to not be afraid of being curious and asking very difficult questions. Some of my characters are really searching, making mistakes. Anyone who’s serious about writing stories, it’s the undertow.”

Above all, she believes in the power of a book’s unspoken message. “I’m trying to say over and over again that it’s okay to be a little outside the center of things. I’m not saying it deliberately, but in the undertow. It’s alright to be the outsider, to stand alone in the world and not be afraid to be alone. I was alone in my childhood. And to not be afraid of being curious and asking very difficult questions. Some of my characters are really searching, making mistakes. Anyone who’s serious about writing stories, it’s the undertow.”

Sarah and David continue to be voracious readers, with two or three books going at once. When asked about their personal library, David stands grandly in the parlor and with wide arms gestures toward a 1930s china cabinet, glass bowed and cracked with Sarah’s gardening books. He thinks through the house: “Upstairs, one wall holds fiction books, another biographies, another YA novels. Downstairs, we have a whole room filled with art reference books, photography, monographs. In the parlor, a small wall of picture books. On the third floor, a wall of picture books, another with philosophy books.”

Sarah tells a story about making room for books, then adds, “You cannot put your books in boxes and store them in a storage area and love them the same way. You need to have them out with you so you can see them and go to the book shelf and know where they are, like you know where your children are when they’re young. My books and I are connected with umbilical cords no force could cut. It’s the craziest thing with book lovers.”

Books have been a healing force for each of them on their journeys. And now, husband and wife, artist and writer, do the same for others. Sarah says, “That is what writers and artists do. We change the world, one word, one sentence, one reader, one picture at a time.”

Web: www.DavidSmallBooks.com

Picture books by Sarah Stewart and David Small together:

The Money Tree (Farrar Straus Giroux, 1994)

The Library (Farrar Straus Giroux, 1995)

The Gardener (Farrar Straus Giroux, 1997)

The Journey (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2001)

The Friend (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004)

The Quiet Place (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2012)

David’s graphic novel memoir: Stitches (W.W. Norton, 2009)

David has also illustrated other books, including the 2001 Caldecott Medal winner So You Want to Be President? by Judith St. George

Karen Pavlicin-Fragnito, publisher of Books Make A Difference, writes and speaks internationally. Connect with Karen on Twitter, Facebook, Web, or email.

This article was first published May 2013.

What a lovely interview. Thank you so much for sharing. I have been a huge fan of David Small’s for years and am just now really finding Sarah’s work too. My husband and I are both artists and this is very inspiring to me about marriage and work and life. Thanks again.

(threebooksanight.com)

Reading Sarah’s books are like walking through parted voracious waters, with looming dangers held at bay as you ‘walk’ on risky new sands, taking each sentence step cautiously, winding you, leading you, gently and safely, to uncovering some unknown eyeopening truths about life, while David’s pictures zero in on each scene with uncanny, bold, emotional honesty. The beautiful pairings of these two – is a true world rarity…