For more than ten years, translator Lucia Graves had been translating her father’s poems and novels from English to Spanish or Catalan. On December 7, 1985, she was living and working in Barcelona and thirty-four words stood between Lucia and the completed translation of her father’s book, Wife to Mr Milton. As she searched for the right words, she sensed her father’s voice. She found the words she needed, and completed the translation at around ten in the morning. At about that same time, across the Mediterranean on the island of Majorca, her father, famous poet, scholar, translator, and writer Robert Graves was taking his final breath.

“I suppose there’s a fine line between extraordinary coincidences,” Lucia says, “and something more akin to magic. I had always been very close to my father, and I took this to be his way of bidding me farewell.”

The Making of a Translator

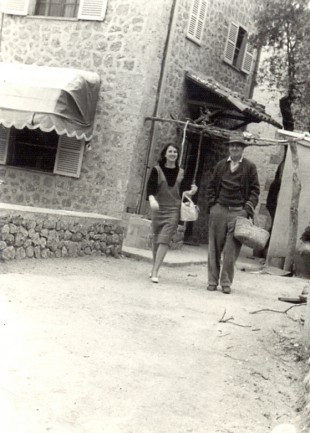

The Graves family moved to the island of Majorca when Lucia was three years old. She says, “Spain is my ‘mother culture’–the culture in which I feel most at home—whereas, English is my mother tongue.” The child of a British family in Spain, Lucia spoke English in their home, but she lived like a Spaniard, speaking Majorcan (a variant of Catalan) with the locals and formal Spanish while in school.

“I slipped in and out of my three languages as one enters and exits different-coloured rooms in a house,” Lucia writes in her memoir, A Woman Unknown: Voices from a Spanish Life. “This excitement of moving between languages was the mainspring of my life.”

Until her teenage years, when she began her formal British education, she hadn’t considered the complexity of the life she was living. Frustration emerged when she came to realize the fracturing that happens while living a trilingual life. While attending a boarding school in Geneva, she began to grasp her father’s fame as a British writer. Strangers seemed to know him and his writing better than she did, and this annoyed her. She decided to read his work. As she realized how difficult it was for her to navigate the challenging text of her father’s prose, she says, “I began to see that being trilingual meant I had never been able to focus fully on any one of my languages, that each one covered only particular areas of experience, and as a result I could not express myself fully in any of them.”

The challenge of speaking, thinking, and writing in three languages compelled Lucia to pursue further study about ways to make use of all of them. Of her university years at Oxford, she writes, “For the first time since my British education had begun, I was accepted by my peers as one of them, and felt comfortably poised between my two worlds.”

Working in Translation

Lucia’s professional career as a translator started in 1971 when she was commissioned by a Barcelona publisher to translate her father’s novel Seven Days in New Crete (Watch the North Wind Rise in the US).

“The one advantage of translating my father’s work,” Lucia explains, “was that I could hear his speaking voice when I read the written word, so I was able to discern any particular emphasis or nuance that might occur in a passage. This helped me understand what ‘layers of meaning’ it was most important to preserve.”

The transition from his voice to hers happened partially because the words were transforming from English to Spanish, but there was a personal transference, too.

Lucia writes in her memoir, “The closer I came to my father through his books, the further apart he grew from me in real life.” While translating her father’s work, Lucia was forced to lean mostly on her recollection of his voice and her growing talent as a translator. Starting in about 1975, Robert Graves had begun to lose his memory, and Lucia lost her ability to bounce ideas off her father as she translated his work.

Lucia writes in her memoir, “The closer I came to my father through his books, the further apart he grew from me in real life.” While translating her father’s work, Lucia was forced to lean mostly on her recollection of his voice and her growing talent as a translator. Starting in about 1975, Robert Graves had begun to lose his memory, and Lucia lost her ability to bounce ideas off her father as she translated his work.

She was perfectly prepared to be the means through which stories moved between and among cultures. She found herself a bit lost in that world, however. Because of the ease with which she travelled through all of those words/worlds, she began to occupy a space only translators might fully appreciate.

“I think it’s vital for a translator to experience his or her target language or languages in a day-to-day situation—at some point of their lives at least,” she explains. “You can also lose touch with your mother tongue if you’re kept away from it for too long. It’s a question of maintaining both languages alive at all times.”

Great stories depend largely upon the language in which they are written, but effective translation can bring those stories to life in a new way. It is a journey uniquely travelled by translators and can often be all-consuming.

“It is always a journey,” Lucia says. “Every book you translate provides a new place to explore, removing you from your own everyday world. The destination is set out for you in the original text. You need to be able to picture it in all its detail, then aim to reach it in a different language. The mind opens and you try to keep the original picture well focused. I sometimes forget parts of books I’ve read, but I never forget the books I’ve translated.”

Lucia has translated more than thirty volumes. She is the translator for Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s worldwide bestselling novels, among them The Shadow of the Wind and The Angel’s Game. Accompanied frequently by dictionaries and text, Lucia considers translation to be less lonely than other writing ventures.

“Translation is perhaps a little less solitary because you’re in the constant company of the author,” she shares. “It’s important that you like the work you’re translating. Dictionaries become companions of sorts, too—going from one to another is like speaking to different people.”

Lucia takes seriously her work to render the author’s full intent with the original writing. She recognizes the importance of understanding and maintaining the style of the original language, including protection of what she terms, “its socio-historical DNA.”

“For my father’s Wife to Mr Milton ,” she explains, “ written from the point of view of a seventeenth century woman in her contemporary English, I used the earliest Spanish dictionary I could find, an early eighteenth century Spanish dictionary, and surrounded myself with seventeenth century Spanish texts, so as not to let any modern words or idioms slip in. Another rule is to beware of being too literal; sayings, proverbs, and some expressions need good equivalents, not translations, and jokes can fall flat if translated literally. At all times, the translator must aim to make the reader feel comfortable and forget they’re reading a translation.”

In addition to the textual tools she uses while translating, Lucia plays a lot of music while she writes and translates.

“Sometimes a particular work will accompany me throughout a project,” she says, “and of course, one must always be aware of the sound and rhythm of language, not just when translating poetry or song lyrics, but even when translating prose.”

Writing to be Translated

After twenty years in Barcelona, Lucia moved from Spain to London in 1991. Since moving back to the land of her mother tongue, she has continued doing translations (now mostly into English) but has also chosen to spend time on her own writing. She wrote her memoir in the late 90s. Most comfortable with the language she spoke in her childhood home, Lucia wrote her memoir originally in English and later translated it into Spanish.

“I find self-translation a rather strange, slightly uncomfortable experience; the line between author and translator becomes blurred,” she says.

Following her memoir, Lucia published her novel The Memory House. The historical fiction novel set in fifteenth century Spain was originally written in English, but first published in her own Spanish translation. It has since been translated by others into Turkish and French.

Lucia is currently working on another story set in fifteenth century Spain, and she looks forward to continuing to learn more about Spain and its rich history while exploring her unique voice that has grown out of translation.

It is difficult to imagine all of the nuances and layers of a woman who has lived a life searching for words to bridge the gaps between languages and cultures. There are parts of her world that she knows are untranslatable. For all the words she has successfully found in her role as a translator and writer, she admits in her memoir, “things did get lost in translation and…there was little one could do about it.”

Books that have Made a Difference for Lucia Graves

Lucia shares her most treasured childhood reading memories: “I grew up without television or radio, so books were our main source of home entertainment. My mother used to read to us, a chapter a night. She was a wonderful reader. We’d sit on the sofa before bedtime and listen, enthralled. And, of course, we read our own books, too. I remember a whole set of fairy tales, each volume bound in a different colour, and the beautifully illustrated Josephine’s Birthday by Mrs H.C. Cradock; also the E. Nesbit novels, The Phoenix and the Carpet being my favourite. Reading was a way of stepping into the English world I had left behind. It was very special. I paid great attention to the print and the quality of the paper.”

Lucia’s favorite books about translation include: “Douglas R. Hofstadter’s Le Ton beau de Marot, an amazing book, so inspiring, always on my desk. And Lost in Translation by Eva Hoffman, a book about what happens when you move from one culture and language to another— brilliant.”

Books by Lucia Graves:

A Woman Unknown: Voices from a Spanish Life

The Memory House

Photo: Lucia and Robert Graves circa 1960. Photo courtesy of Lucia Graves.

Just picked up your book a woman unknown in a small bookshop on a island in the west of ireland. i was surprised to find a book shop only 160 people living there. charming shop, handpicked books. love the book,

Dear Ms. Graves,

I recently became a great fan of Zafon’s

wonderful novels which you so beautifully

translated. Brava! Just into “the Prisoner

of Heaven, came shock, amazement and a fit of giggles. The Man In Black stops in at

a Barcelona bookseller, and asks to see

a particular volume in its cabinet of rare works –identified as The Count of Monte Christo illustrated by Arthur Rackham! Alas, no such book exists. AR’s bibliographer and my humble self can confirm this. (I have

the entire canon of Rackham treasures and

most of his pre 1906 work.) So, I am full

of questions about Zafon’s attribution. Was

it a mistake or just another mysterious incident, typical of his work? Perhaps you can throw some light on this. Again, I have fallen in love with his books that you’ve brought to life for me.

With kind regards,

Nick Wedge

Hola Lucía. Acabo de publicar mis recuerdos de mocedad. (Barrio Gótico) Este verano, si quieres te lo acambio de A Woman Unknown

Hola Lucía. acabo de publicar mis memorias (Barrio Gótico) Este verano te las daré a cambio de las tuyas (a woman unknown ? )